When I returned home from school for the summer,

I did so with less than twenty dollars in the bank. It was the same every year,

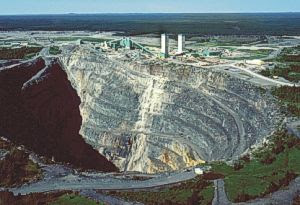

so it’s no surprise that my first was no exception. My working at Kidd Creek

during the summer made no difference, either. No matter how much money I made,

I was always in need of a loan from my parents come March, and upon arriving

home for the summer. I always paid them back, usually with my income tax

return, but sometimes with a portion of my first couple pays, as well. You’d think

I’d have learned restraint in the following years, but back then I can’t say I

was much of a long-term planner.

That first summer back from college was a big one for me. There was money to be

made (my first well-paying job), savings to be stowed for the coming year,

Roxanne to exorcise from my soul, my sister’s wedding, and my near fatal car

accident (see prior early memories if you haven’t been keeping abreast of these

ongoing missives).

I arrived home, having already made up my mind to leave Haileybury and continue

my scholastic career in Sudbury at Cambrian. I’d applied and was accepted. Now,

all I needed to do was make and save some money. I didn’t even need to make

arrangements for a car pool. My neighbor, George Miller, asked around and set

me up. But first, I had to celebrate my homecoming…not that I’d actually ever

really left. Like I said, I wasn’t much of a long-term planner back then.

My first day of work, I was out on my curb waiting for my ride. The car pool

pulled up, the Econoline’s side panel slid open, and I was ushered in by a van

full of strangers. Shy at first, I kept to myself, observing these grown men I

would be travelling to work with for the coming months. They were a grizzled

bunch, not one of them taking the time to shave that morning. They were gruff,

loud, eager to make the smallest of talk. Half an hour later, I spilled out

with the rest of them, and made my way to training, following the arrows penned

on sheets of paper taped to the wall to guide me. I sat through induction, was

given a locker, a payroll number, sheets to sign. I was introduced to my

Captain (General Foreman) and my Shifter (Front Line Foreman). And then I was

told that I’d be working in the field, away from my crew for a week, scaling

and bolting the back (the ceiling) of a newly fired round on 40-1. Too much

mining talk? Confused? So was I.

The next morning, suited up in coveralls, boots, belt and hard hat, we were

taught how to collect the cap lamps allotted us, and where to wait for the

cage. New to this, we were herded together like the inexperienced sheep we

were. The pager squawked inexplicable instructions (I, personally, could not

make out a word that was said), and those in the know stood up and headed to

the shaft. We waited like sensible sheep for our turn. And when it came, we too

inched our way to the shaft, onto the cage, jammed in as tight as can be, lunch

pails held tightly between our legs. The door crashed down, bells were rung to

the hoistman, and we descended into the black depths. Silence descended too,

quiet mutterings here and there. Over those, the cage rattled and scraped the

guides. Our breath steamed from us, illuminated by already affixed headlamps,

their beams sweeping about. Never in another’s eyes; to do so risked having the

lamp rapped and smashed by an irate wrench. The cold of the upper mine escaped

the cracks, replaced with a heavy heat as each level rushed past in a piston

pressed cushion of air. The cage shuddered and shook with each passing, then

slowed, then inched, then stopped as the cagetender indicated: one bell, stop,

then three, men in motion.

2 Mine was hot; deeply humid, not as well ventilated as 1 Mine. The heading was

quiet, stifling. At least until the scaling and bolting began. Then, rocks

crashed to our feet after prying, drills blared the loudest roar I’d ever

heard. The air smelled of oil and nitrates and resin and sweat. And cigarettes.

Fog enveloped us, we each silhouetted in backlight. Eerie. Beautiful. You’d

have to see it to understand.

I joined my crew the next week. Bob Semour, Charlie Trampanier, Rod Skinner,

Brian Wilson, among others. I was to man the picking belt for the summer, part

of the crusher crew. But I was also to work with the construction gang on

occasion, when needed. Building walls, pumping cement. On the belts, there was

shoveling to do, every day there was shoveling, scrap to be picked up, and

dumped in rail cars, and pushed by hand to the station. Lean into it, shove

hard to get it going, pick up speed or we’d never get it through the S turn and

it would grind to a halt, and we’d have to pry it on, or push it halfway back

to try again. I learned important lessons. You fucked it, you fix it, being the

most important. Always wear your safety glasses when the boss is around. Sit on

your gloves or you’ll get piles. Lift this way. Watch out, that’s dangerous.

Don’t touch that. I learned the thrill of setting off a blast. The boredom of

guarding. Always bring a book.

And I learned that you can earn the nickname Crash when you’ve been in a car

accident that caused you to miss a week’s work. And how happy they are to see

you after that accident too, if stiff and limping. And how your boss says,

you’re light duty this week, Crash. I want you to drive that pick-up. I was

terrified at the prospect, but he said, better get back on that horse, or it’ll

scare you the rest of your life. I did. It didn’t.

Paychecks, parties.

And that summer I started smoking. At 19. What was I thinking? I wasn’t. Idiot!

You’d think I’d have been immune to beginning after 19 years of having not.

You’ll note a theme that runs through these early years, these early memories.

Thinking was not foremost in my mind, then. I was at the Empire Hotel, in early

enough that the sunlight still found its way into its narrow smoky twilight. I

found Astra and Alma Senkus already there. They called me over. They had a

couple beers before them, smokes lit. I watched. I wondered what it would be

like to take a drag, to inhale and blow that long steam of smoke across the

table. And I wanted to impress the twins. Secretly, I wondered what it would be

like to lose my virginity to twins. So, I asked for one. They were reticent,

joked with me about how addictive smoking was. But I was a man, under the spell

of wanting to impress attractive women. I insisted. They gave me one. I

inhaled, coughed as expected, inhaled again, coughed less. And grew somewhat

lightheaded. On my second beer, I asked for another.

As you can imagine, this was another one of those worst decisions of my life.

And in case you’re wondering, no, I did not lose my virginity to the Senkus

twins that night.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Popular Posts

-

I arrived the day before the Nile Tour was set to begin, and booked into our hotel, the Marriott Mena House. Originally a private hunting lo...

-

Heroes. Do we ever really have them; or are they some strange affectation we only espouse to having? Thus, the question arises: Did I, g...

-

I made mention earlier that Jean Rhys wrote a parallel novel to Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. I also made mention that it is a worthy ed...

The Quincunx

I feel a sense of accomplishment, having finally read this book. It languished on my shelves for about 30 years. That’s a long time. One won...

No comments:

Post a Comment