|

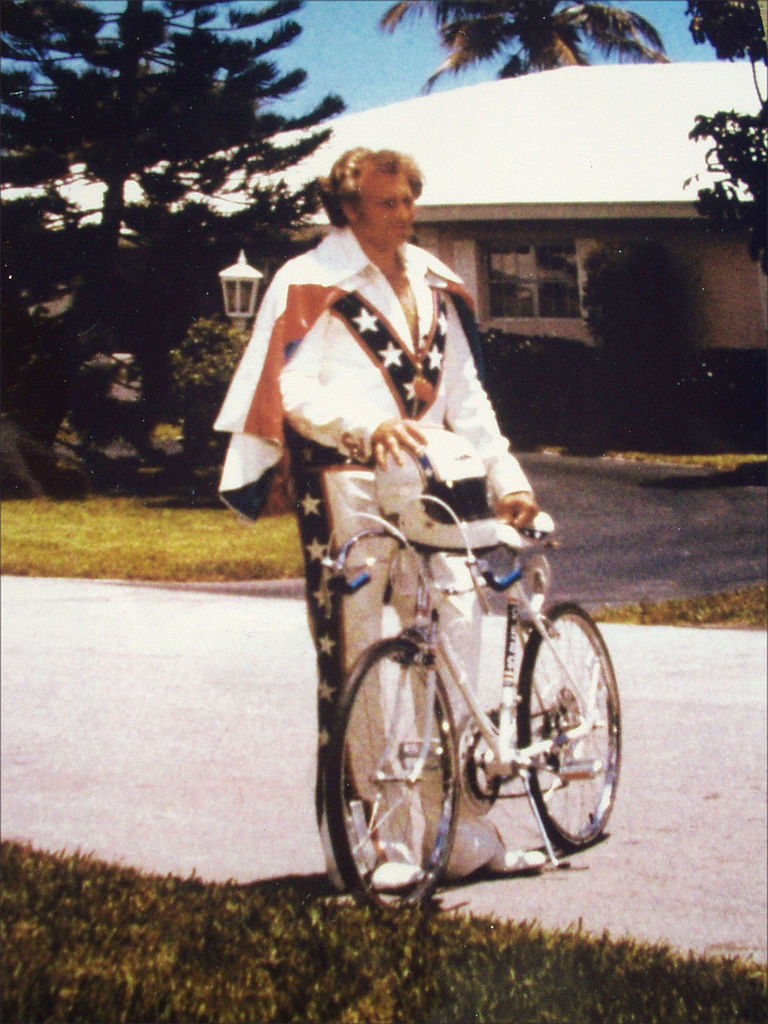

| Not me, but that's the very image of my CCM Mustang |

I hit a parked car on my first solo ride with it. Years later I ended up in the hospital from a concussion while riding it (but that's another story that will follow in due course), but in between I hit the roads and trails behind Pinecrest School, behind and below where TDH, the Timmins District Hospital, now stands, if it didn't then. There were streams and what we thought of as lakes back there, not to mention hastily erected forts and cut trails, later expropriated and widened by the Mattagami Region Conservation Society, and still in use today (I still walk that trail today). We scampered over Scout and the much further Cherry Rock. They were tall and had precariously perched boulders atop them that made narrow caves that we imagined bears slept in. We waded in those streams, caught minnows, or tried to anyways, chased frogs, searched for snakes, and a little later, stole our first kisses on those trails. Pecks then, certainly, nothing like those that would soon follow. First steps.