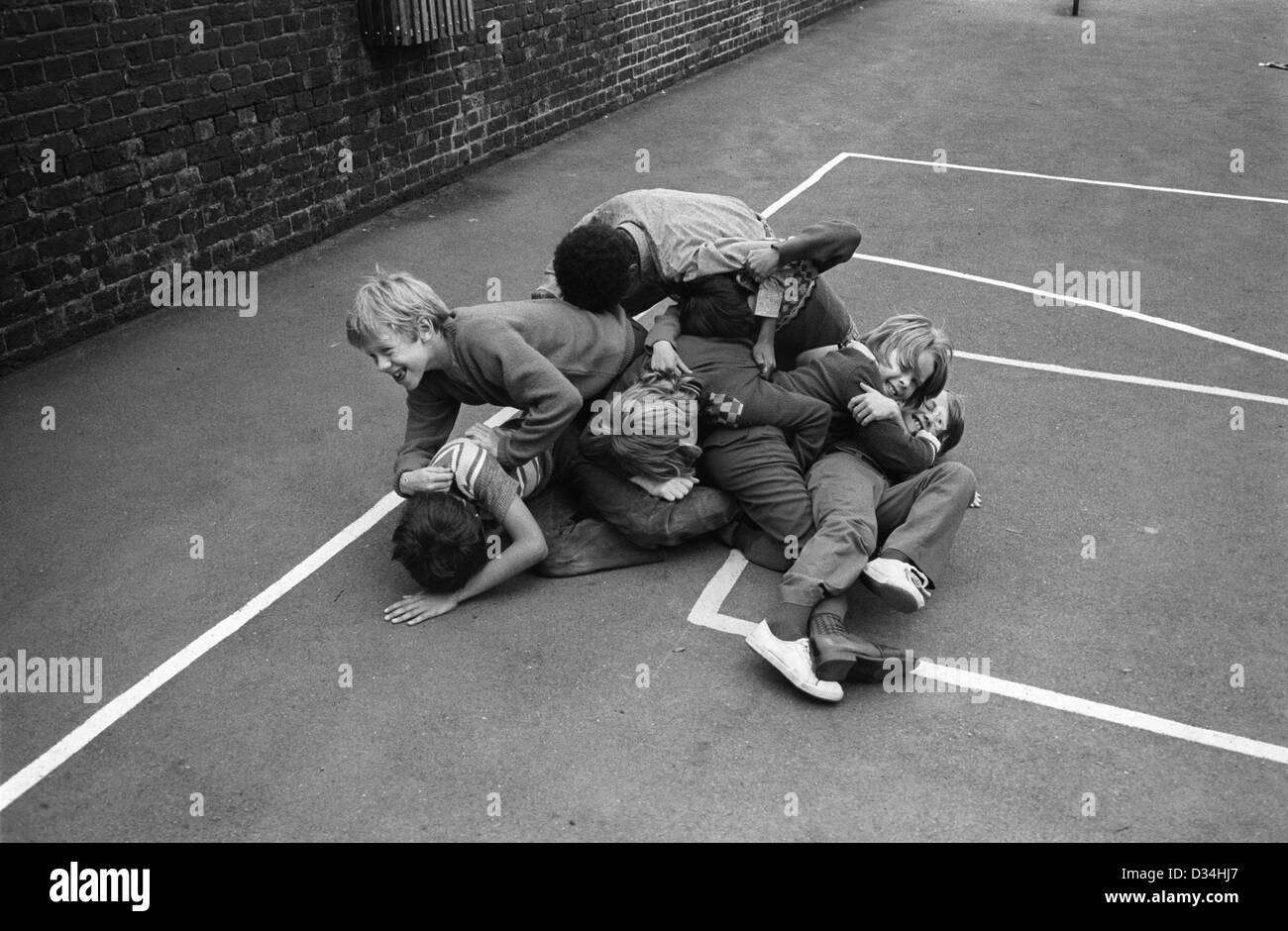

I’m not sure what else to call them, but I recall we had them at both Pinecrest and St. Theresa, where the school made up teams of members of different home rooms and grades, named them particularly cool and evocative names like the blue team, the red team, green, etc., or some such, and set the teams to compete athletically for points. Sort of like team Olympics.

Pinecrest was held in the warm spring months, so the sports were relay races, high jumps and the sort. I was especially good at the sprints, somewhat good at high jumps, disastrous at throwing events. We’d compete, and the teachers would award the points to the winning teams, and after completing the full circuit of events, the points were tallied and the three teams with the highest scores won gold, silver, and bronze. I don’t remember actually winning a medal, although I do remember once or twice being confused by who actually did win an event, not keeping the actual number of home runs or whatever clear in my head. Paying close attention to details like timekeeping and unmarked scoring was not really my strong suit back then.

St. Theresa’s was held in the winter, but the events were pretty similar. The one I recall most of all was a simple one. One team had to kick a soccer ball through the opposing team, each player in turn, and the team that kicked through the other the most got the points. I knew I would do well at this one. I’d played soccer at recesses since grade 1 and was always good at it. I could always kick long and far, and with reasonable accuracy. There were no other rules than those simple ones; so, when my turn came, I prepared for the kick by setting up the ball on a built up, make-shift tee of snow. I set the ball atop it, stood back, and having already figured out who had guarded their end the worst, decided to kick through them. I decided to keep the angle of the kick as secret as possible to the very end so the other team wouldn’t be able to shift their goal keeping at the last moment, as I’d seen them do, skipped the first couple steps, and then quickly wound up and kicked hard. And realized my mistake the moment I connected with the ball; I’d stacked the tee too high. My instep kicked the ball, not my toe, and the ball went high, not hard and deep as I’d intended. It went oh so high, like a pop-up fly ball in baseball. I watched the ball as it rose, as it seemed to hang in space forever, and I cursed. It was the easiest catch of the event. I didn’t win a medal at that particular Olympics, either.